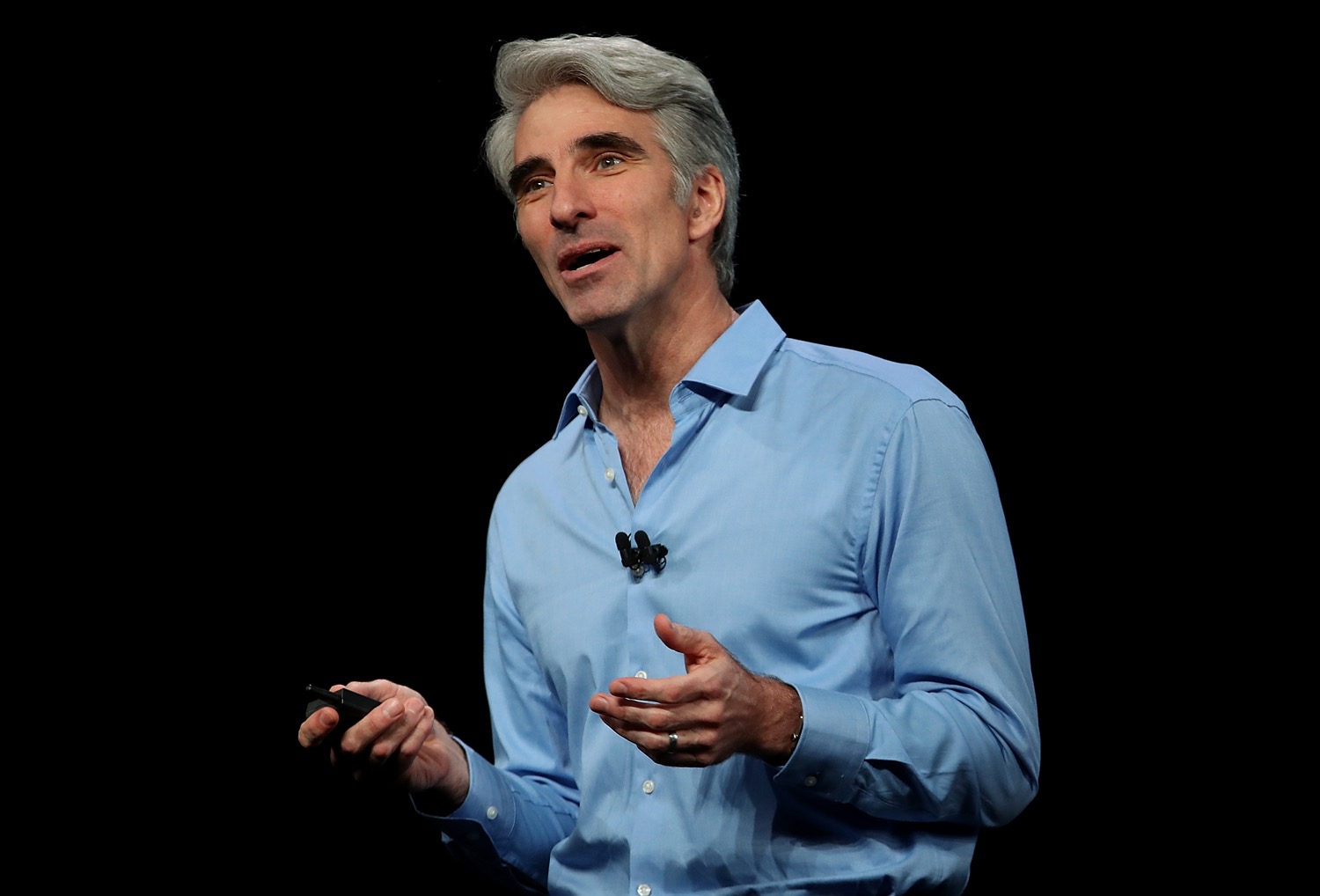

Apple's decision to have iPhones and other Apple devices scan photos for child sexual abuse material (CSAM) has sparked criticism from security experts and privacy advocates—and from some Apple employees. But Apple believes its new system is an advancement in privacy that will "enabl[e] a more private world," according to Craig Federighi, the company's senior VP of software engineering.

Federighi defended the new system in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, saying that Apple is aiming to detect child sexual abuse photos in a way that protects user privacy more than other, more invasive scanning systems. The Journal wrote today:

While Apple's new efforts have drawn praise from some, the company has also received criticism. An executive at Facebook Inc.'s WhatsApp messaging service and others, including Edward Snowden, have called Apple's approach bad for privacy. The overarching concern is whether Apple can use software that identifies illegal material without the system being taken advantage of by others, such as governments, pushing for more private information—a suggestion Apple strongly denies and Mr. Federighi said will be protected against by "multiple levels of auditability." "We, who consider ourselves absolutely leading on privacy, see what we are doing here as an advancement of the state of the art in privacy, as enabling a more private world," Mr. Federighi said.In a video of the interview, Federighi said, "[W]hat we're doing is we're finding illegal images of child pornography stored in iCloud. If you look at any other cloud service, they currently are scanning photos by looking at every single photo in the cloud and analyzing it. We wanted to be able to spot such photos in the cloud without looking at people's photos and came up with an architecture to do this." The Apple system is not a "backdoor" that breaks encryption and is "much more private than anything that's been done in this area before," he said. Apple developed the architecture for identifying photos "in the most privacy-protecting way we can imagine and in the most auditable and verifiable way possible," he said. The system has divided employees. "Apple employees have flooded an Apple internal Slack channel with more than 800 messages on the plan announced a week ago, workers who asked not to be identified told Reuters," the Reuters news organization wrote yesterday. "Many expressed worries that the feature could be exploited by repressive governments looking to find other material for censorship or arrests, according to workers who saw the days-long thread." While some employees "worried that Apple is damaging its leading reputation for protecting privacy," Apple's "[c]ore security employees did not appear to be major complainants in the posts, and some of them said that they thought Apple's solution was a reasonable response to pressure to crack down on illegal material," Reuters wrote.

Phones to scan photos before uploading to iCloud

Apple announced last week that devices with iCloud Photos enabled will scan images before they are uploaded to iCloud. An iPhone uploads every photo to iCloud almost immediately after it is taken, so the scanning would also happen almost immediately if a user has previously turned iCloud Photos on. As we reported, Apple said its technology "analyzes an image and converts it to a unique number specific to that image." The system flags a photo when its hash is identical or nearly identical to the hash of any that appear in a database of known CSAM. Apple said its server "learns nothing about non-matching images," and even the user devices "learn [nothing] about the result of the match because that requires knowledge of the server-side blinding secret." Apple also said its system's design "ensures less than a one in one trillion chance per year of incorrectly flagging a given account" and that the system prevents Apple from learning the result "unless the iCloud Photos account crosses a threshold of known CSAM content." That threshold is approximately 30 known CSAM photos, Federighi told the Journal. While Apple could alter the system to scan for other types of content, the company on Monday said it will refuse any government demands to expand beyond the current plan of using the technology only to detect CSAM. Apple is separately adding on-device machine learning to the Messages application for a tool that parents will have the option of using for their children. Apple says the Messages technology will "analyze image attachments and determine if a photo is sexually explicit" without giving Apple access to the messages. The system will "warn children and their parents when receiving or sending sexually explicit photos." Apple said the changes will roll out later this year in updates to iOS 15, iPadOS 15, watchOS 8, and macOS Monterey and that the new system will be implemented in the US only at first and come to other countries later.Federighi: “Messages got jumbled pretty badly”

Federighi said that critics have misunderstood what Apple is doing. "It's really clear a lot of messages got jumbled pretty badly in terms of how things were understood," Federighi told The Wall Street Journal. "We wish that this would've come out a little more clearly for everyone because we feel very positive and strongly about what we're doing." The simultaneous announcement of two systems—one that scans photos for CSAM and another that scans Messages attachments for sexually explicit material—led some people on social media to say they are "worried... about having family photos of their babies in the bath being flagged by Apple as pornography," the Journal noted. "In hindsight, introducing these two features at the same time was a recipe for this kind of confusion," Federighi said. "By releasing them at the same time, people technically connected them and got very scared: What's happening with my messages? The answer is... nothing is happening with your messages."About 30 photos will trigger action

Apple didn't initially say how many CSAM photos are enough to trigger action by Apple, which will send reports to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children( NCMEC) after manually reviewing accounts flagged by the system to ensure accuracy. Federighi provided details, saying, "If and only if you meet a threshold of something on the order of 30 known child pornographic images matching, only then does Apple know anything about your account and know anything about those images, and at that point, only knows about those images, not about any of your other images," Federighi said. "This isn't doing some analysis for 'did you have a picture of your child in the bathtub?' Or, for that matter, 'did you have a picture of some pornography of any other sort?' This is literally only matching on the exact fingerprints of specific known child pornographic images." Update at 3:25pm ET: Apple released a new document shortly after this article published. It explains that the 30-image threshold was chosen to ensure a false-positive rate of "lower than one in one trillion" for each account. The threshold could change as more evidence is analyzed. "Building in an additional safety margin by assuming that every iCloud Photo library is larger than the actual largest one, we expect to choose an initial match threshold of 30 images. Since this initial threshold contains a drastic safety margin reflecting a worst-case assumption about real-world performance, we may change the threshold after continued empirical evaluation of NeuralHash false positive rates—but the match threshold will never be lower than what is required to produce a one-in-one-trillion false positive rate for any given account." Federighi said the image-matching system being located on user devices instead of on Apple servers is good for privacy, the Journal wrote:Beyond creating a system that isn't scanning through all of a user's photos in the cloud, Mr. Federighi pointed to another benefit of placing the matching process on the phone directly. "Because it's on the [phone], security researchers are constantly able to introspect what's happening in Apple's [phone] software," he said. "So if any changes were made that were to expand the scope of this in some way—in a way that we had committed to not doing—there's verifiability, they can spot that that's happening."Federighi also said the CSAM database "is constructed through the intersection of images from multiple child safety organizations," including the NCMEC, and that at least two "are in distinct jurisdictions." "Such groups and an independent auditor will be able to verify that the database only consists of images provided by those entities, he said," the Journal wrote.

“Nuanced opinions are OK on this”

Alex Stamos, the former chief security officer of Facebook who is now director of the Stanford Internet Observatory, wrote, "[T]here are no easy answers here. I find myself constantly torn between wanting everybody to have access to cryptographic privacy and the reality of the scale and depth of harm that has been enabled by modern comms technologies. Nuanced opinions are OK on this." Security expert Bruce Schneier called Apple's system "a security disaster." "This is pretty shocking coming from Apple, which is generally really good about privacy. It opens the door for all sorts of other surveillance, since now that the system is built, it can be used for all sorts of other messages," he wrote. Apple's assurances that it won't expand the scanning technology to other types of content when governments demand it have not been convincing to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "Apple has promised it will refuse government 'demands to build and deploy government-mandated changes that degrade the privacy of users.' It is good that Apple says it will not, but this is not nearly as strong a protection as saying it cannot, which could not honestly be said about any system of this type," wrote Kurt Opsahl, the EFF's general counsel and deputy executive director. "Moreover, if it implements this change, Apple will need to not just fight for privacy but win in legislatures and courts around the world. To keep its promise, Apple will have to resist the pressure to expand the iMessage scanning program to new countries, to scan for new types of content and to report outside parent-child relationships." Opsahl outlined his concerns on Wednesday in a post titled, "If You Build It, They Will Come: Apple Has Opened the Backdoor to Increased Surveillance and Censorship Around the World." The US government has pressured Apple for years to provide a "backdoor" to its encryption. Opsahl noted that demands for encrypted data often come from democratic countries, and "[i]f companies fail to hold the line in such countries, the changes made to undermine encryption can easily be replicated by countries with weaker democratic institutions and poor human rights records—often using similar legal language, but with different ideas about public order and state security, as well as what constitutes impermissible content, from obscenity to indecency to political speech." The Constitution will prevent "some of the worst excesses" in the US, because "a search ordered by the government is subject to the Fourth Amendmentm" and "any 'warrant' issued for suspicionless mass surveillance would be an unconstitutional general warrant," Opsahl wrote. Still, Congress could pass new laws requiring access to more user data. "With this new program, Apple has failed to hold a strong policy line against [potential] US laws undermining encryption, but there remains a constitutional backstop to some of the worst excesses," Opsahl wrote.EFF predicts big problems in authoritarian countries

Those constitutional protections obviously aren't available in all countries. While Apple's new system will be US-only at first, Apple has users all over the world and faces pressure from many governments, Opsahl wrote:It is no surprise that authoritarian countries demand companies provide access and control to encrypted messages, often the last best hope for dissidents to organize and communicate. For example, Citizen Lab's research shows that—right now—China's unencrypted WeChat service already surveils images and files shared by users and uses them to train censorship algorithms.Opsahl noted that "the Five Eyes—an alliance of the intelligence services of Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—warned in 2018 that they will 'pursue technological, enforcement, legislative or other measures to achieve lawful access solutions' if the companies didn't voluntarily provide access to encrypted messages. More recently, the Five Eyes have pivoted from terrorism to the prevention of CSAM as the justification, but the demand for unencrypted access remains the same, and the Five Eyes are unlikely to be satisfied without changes to assist terrorism and criminal investigations too." Countries with poor human rights records "will nevertheless contend that they are no different" from democratic ones, he wrote. "They are sovereign nations and will see their public-order needs as equally urgent. They will contend that if Apple is providing access to any nation-state under that state's local laws, Apple must also provide access to other countries, at least, under the same terms." Federighi argued that Apple won't be able to "get away with" conducting surveillance for governments. "Let's say you don't want to just rely on Apple saying no [to government requests]," he told the Journal. "You want to be sure that Apple couldn't get away with it if we said yes. Well, that was the bar we set for ourselves in releasing this kind of system. There are multiple levels of auditability, we're making sure you don't have to trust any one entity or even any one country as far as what images are part of this process."