The US House of Representatives today voted to restore Obama-era net neutrality rules, approving a bill that would reverse the Trump-era FCC's repeal of rules that formerly prohibited blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization. The vote was 232-190, with 231 Democrats and one Republican supporting the bill, and 190 Republicans voting against it. Four Democrats and six Republicans did not vote.

The bill isn't likely to become law, though, as it could be either blocked by the Republican-controlled Senate or vetoed by President Trump. White House staff on Monday recommended that Trump veto the bill, claiming that the net neutrality repeal spurred new broadband deployment—even though Federal Communications Commission data doesn't actually support that conclusion.

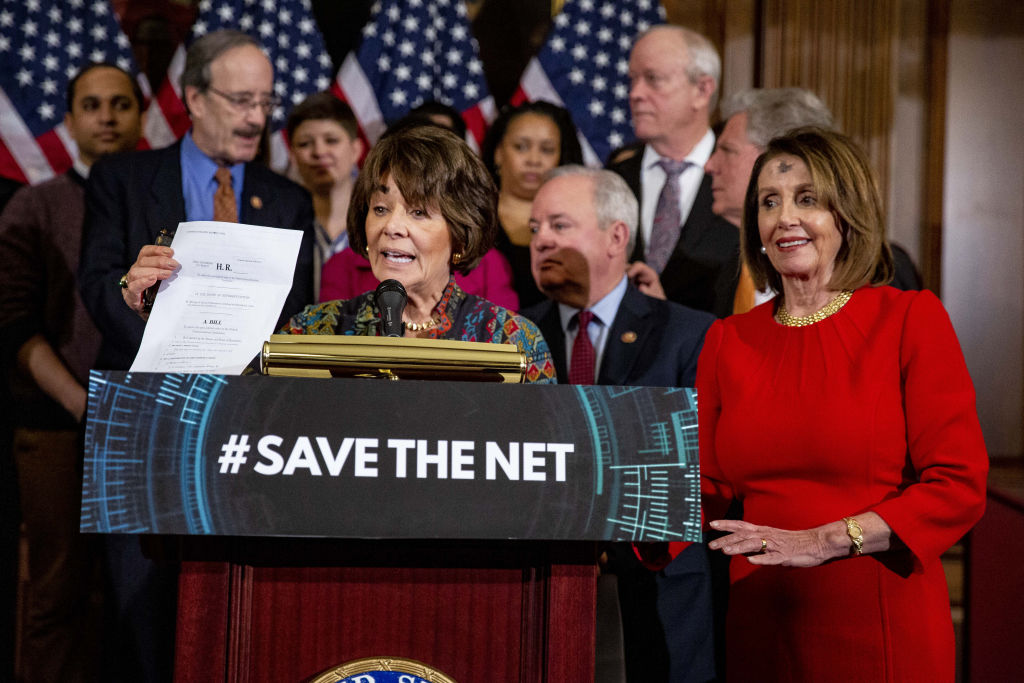

The Democrats' "Save the Internet Act" doesn't even seem likely to reach Trump, as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) declared it "dead on arrival."

Passage in the House was expected, as Democratic leaders pushed the bill and Democrats have a 235-197 majority. Debate on the House floor began yesterday and concluded today.

"The Save the Internet Act ensures that consumers have control over their Internet experience, rather than Internet service providers [controlling that experience]," Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) said yesterday. "This is just common sense. Each of us should be able to decide what videos we watch, which sites we read, and which services we use. Nobody should be able to influence that choice—not the government and not the large companies that run the networks."

Democrats also argue that net neutrality rules boost the economy by ensuring that small businesses can reach consumers over the Internet at the same speeds as large businesses that would be able to pay for prioritized access.

Rep. Bill Posey (R-Fla.) was the only Republican to vote for the bill.

GOP slams “socialist agenda”

Republicans introduced their own, weaker net neutrality bills, and tried to gut the Democrats' proposal with amendments that would exempt many broadband providers and broadband services from net neutrality rules. But Democrats held firm on a bill to fully restore the net neutrality rules that were in place from June 2015 to June 2018.

Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.) argued that the Democrats' net neutrality bill is "another plank in their socialist agenda that would regulate the Internet as if it were a monopoly utility" and a "government takeover of the Internet."

Walden also claimed that the bill could let the government take over and manage private broadband networks, dictate where and when new broadband networks must be deployed, tax the Internet, regulate speech on the Internet, and limit the full potential of 5G. In reality, the Democrats' bill would simply reinstate the net neutrality rules that were in place between 2015 and 2018, and none of those things happened during that time.

"What my friend refers to as a takeover of the Internet, we call protecting consumers, and that's what we're asking the FCC to do," Rep. Mike Doyle (D-Penn.) said yesterday.

Rep. Steve Scalise (R-La.) also suggested that the net neutrality bill does more than it actually does, claiming the net neutrality debate is "a battle of individual freedom vs government control—should you have the choice to decide which provider you want to get your Internet service from?" Despite what Scalise said, there's nothing in the bill that would prevent consumers from switching ISPs—if they have a choice at all, and many American's don't.

Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) said that anyone who thinks net neutrality rules aren't needed should talk to Santa Clara County firefighters, whose "unlimited data" plan was throttled by Verizon while they were fighting a wildfire last year.

"If you think that the ISPs haven't misbehaved, talk to the firefighters of Santa Clara County," Eshoo said. "Talk to them. They were fighting the worst fire in California's history. They were being throttled. They called Verizon and Verizon tried to sell them an upgraded plan as they were trying to save lives." (While the net neutrality rules did not prohibit throttling of unlimited data plans when consumers hit monthly "de-prioritization" usage thresholds imposed by carriers, the rules did allow Internet users to complain to the FCC about unjust or unreasonable prices and practices.)

While some Republicans claimed they support net neutrality and faulted Democrats for not compromising, Doyle pointed out that Republicans didn't pass a net neutrality law even when they controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House in 2017 and 2018.

Tough path in Senate

The Senate voted to reverse the FCC's net neutrality repeal in May 2018, when three Republicans bucked party leadership to join Democrats in a 52-47 vote. But Republicans had a slimmer Senate majority last year, and Democrats were able to force a vote only by pushing a Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolution instead of a regular bill.

CRA resolutions, which reverse federal agency decisions, need only a simple majority to force a floor vote and ensure passage. But CRA resolutions can only be passed in the same Congressional session in which the agency decision was made. Because a new Congressional session began in January, a CRA resolution nullifying FCC Chairman Ajit Pai's December 2017 repeal order is no longer an option.

This time around, the Senate bill to restore net neutrality rules must go through the normal committee process, which is controlled by Republicans. Just getting the bill to the Senate floor for a final vote will thus be significantly more difficult for Democrats than it was last year.

Last year's CRA resolution failed in the House, as Republicans still held a sizable majority at the time.

No blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization

Fully restoring net neutrality rules with the Democrats' bill would generally prohibit both home and mobile Internet service providers from blocking or throttling lawful Internet traffic, and from striking paid prioritization deals. ISPs could still throttle consumers' overall speeds based on which data plans they buy, but ISPs wouldn't be allowed to discriminate against particular websites or online services.

The Democrats' bill would also reinstate other consumer protections that used to be enforced by the FCC, such as a requirement that ISPs be more transparent with customers about hidden fees and the consequences of exceeding data caps.

There is good news for ISPs, though. The amended version of the bill sent to the House floor by the House Commerce Committee attempts to lock the FCC's 2015 order in place, including the FCC decisions to forbear from applying other Title II common-carrier rules such as rate regulation and last-mile unbundling. The Democrats' bill could thus prevent current and future FCC majorities from repealing net neutrality rules and from imposing other rules that the Obama-era FCC declined to impose.

The bill text says this "would have the effect of permanently prohibiting the Commission from reversing any decision within the [FCC's 2015] Declaratory Ruling and Order to apply or forbear from applying a provision of the Communications Act of 1934 or a regulation of the Commission."

In that 2015 net neutrality order, the FCC explicitly said that its forbearance decision "includes no unbundling of last-mile facilities, no tariffing, no rate regulation, and no cost accounting rules." The Democrats described their bill as an attempt to lock that decision into place permanently.

The bill "permanently prohibits the FCC from applying provisions on rate-setting, unbundling of ISP networks, or levying additional taxes or fees on broadband access," Doyle said.

But while this bill would prevent the FCC from applying existing Title II-based rules to broadband, it might still be possible for future FCC majorities to write entirely new common-carrier regulations for broadband by starting a new, separate rulemaking proceeding.

Since 2015, broadband industry lobbyists and Republicans in Congress have repeatedly said they support net neutrality rules but not the FCC's use of its Title II authority to impose those rules. They've argued that the use of Title II could eventually lead to the FCC imposing broadband price caps and other rules not specifically related to net neutrality.

At the very least, the Democrats' bill would make it more difficult for future FCCs to impose rate regulation and unbundling. Despite that, Republicans and ISPs continued to oppose the Democrats' net neutrality bill.

Democrats did support one Republican amendment that would require the FCC to list all of the rules and regulations that it forbore from in the 2015 net neutrality order. The FCC said in its net neutrality order that it declined to apply more than 700 regulations to broadband, but it did not release a list of all of them.

Another amendment approved would require the FCC to report back to Congress after one year to describe any net neutrality investigations and enforcement actions the commission has launched. Another approved amendment would require the FCC to evaluate and address problems in data collection on broadband availability, because the FCC's broadband deployment data is imprecise and often exaggerates availability.

Republicans’ unyielding opposition

Republicans argued that the Internet works fine without net neutrality rules.

"I haven't seen any nefarious Internet shortages or blockages in recent days," Rep. Rob Woodall (R-Ga.) said, noting that the House proceedings were streamed online despite the lack of net neutrality rules. "It's going right through the pipes the way it always has."

"It's unfortunate that so many people are afraid of Internet freedom," Woodall also said, apparently referring to freedom from net neutrality rules for ISPs.

Rep. Michael Burgess (R-Texas) claimed that 5G wireless services will eliminate the need for net neutrality rules "because latency for all content will be almost zero." (In reality, Verizon just launched mobile 5G in small parts of Chicago and Minneapolis and said latency would be nearly 30 milliseconds.)

"The Internet for decades has thrived because it was not under the heavy hand of government," Burgess said.

While Republicans in Congress are staunchly against the Democrats' proposed net neutrality rules, Republicans in general are not. After surveying nearly 1,000 registered voters last year, the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland reported that "eighty-six percent oppose the repeal of net neutrality, including 82 percent of Republicans and 90 percent of Democrats."