Google-parent Alphabet is shutting down its power-generating kites company Makani, the first closure of a so-called moonshot project since founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin stepped back from management in December.

Sundar Pichai, who took over as Alphabet chief executive, is under pressure to stem losses from the company’s “Other Bets” segment, which includes endeavors such as self-driving cars and Internet-providing balloons. Other Bets lost $4.8 billion last year—widening from a $3.4 billion loss in 2018.

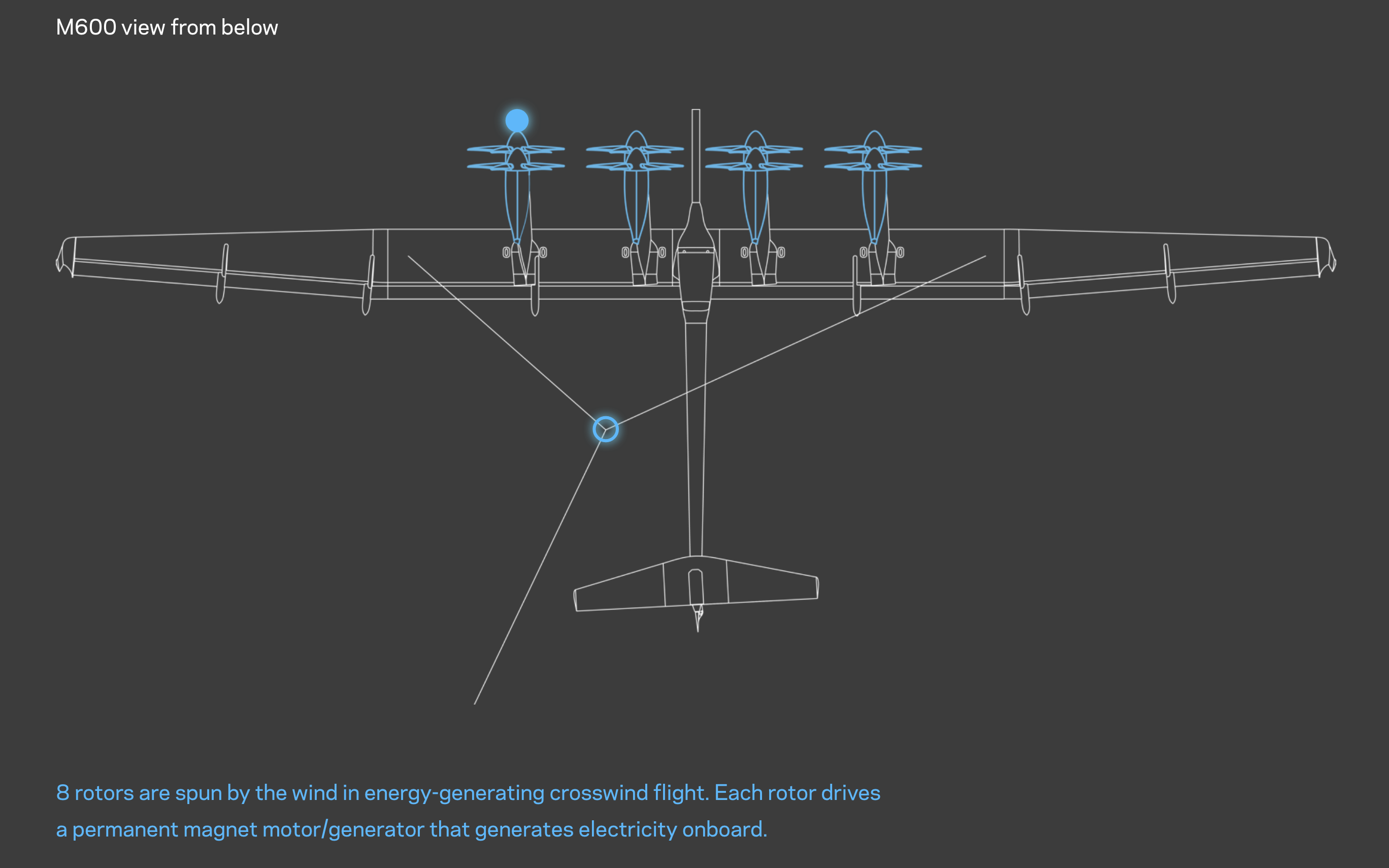

Makani was acquired in 2013 and taken into the experimental “X” lab. It was developing airborne wind turbines that could be tethered to floating buoys, removing the need for the expensive ocean bed structures needed to support permanent turbines.

“It’s been a very hard choice for us,” said Astro Teller, chief executive of X, speaking to the Financial Times on Tuesday.

“Our estimate of the rewards for the world, the reward to Alphabet, and the risks and costs to get there... they change over time. It’s part of my job to assess that and make sure that we’re picking the best ones we can for Alphabet to spend its money on.”

Alphabet would not confirm the size of Makani, only saying it consisted of “dozens” of employees that it hoped it could be reassigned to other climate change-related work at Alphabet. A small team will stay on for a few months to collate Makani’s research.

Makani’s kites were designed to fly as high as 1,000ft, or about 300m, above the water while attached to floating buoys weighed down with anchors, instead of the full ocean platforms required to support typical offshore wind farms. It was hoped that Makani’s technology could be used in areas of the ocean too deep to set up fixed wind turbines and where winds are strongest.

As is typical for X companies that show potential for commercialization, Makani was spun out of the lab in February last year following an undisclosed investment from Royal Dutch Shell. In August, Makani held its first test flight off the coast of Norway.

But Alphabet decided the opportunity to greatly disrupt the energy sector had begun to dwindle. While Makani at first felt it could provide a competitive advantage by using its technology on land and in shallow water—as well as deep water—advancements in competing technologies meant that was likely no longer the case.

“That’s very sad for Makani,” Teller said. “But it’s really great for the world.”

An EU report published in 2018 concurred with Alphabet’s assessment. “The technology still has a long way to go before it can reach commercialization,” it read, noting that challenges remained in demonstrating the reliable, autonomous operation that would make the concept viable.

Shell said it was “exploring options” to take on Makani’s technology. “Offshore wind has the potential to reach the large-scale generation capacity that society needs to transition to a lower-carbon energy system” said Dorine Bosman, vice-president of Shell Wind Development.

“We believe that Makani remains one of the leading airborne-wind technologies in the world and we are exploring options to continue developing the technology within our New Energies strategy.”

Alphabet pointed to other climate change projects within the company, such as drone delivery firm Wing, as an indication the company was not changing its focus. Teller told the Financial Times that investment in moonshots would remain strong under Pichai and Ruth Porat, Alphabet’s chief financial officer.

“The appetite from Sundar and from Ruth for us to continue to make smart, exciting bets about the future has, if anything, gone up,” Teller said.

“Part of the reason that they’re supportive for us to continue to do that is when something doesn’t make sense, we make the hard choices to not continue doing them. That’s what buys the ongoing support from Alphabet.”

© 2020 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved.

FT and Financial times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

FT and Financial times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.