On Wednesday, as NASA continued to press lawmakers to support an accelerated plan to return humans to the Moon, the space agency began distributing a document titled Why Gateway? in defense of a return. The document summarizes why NASA thinks a space station near the Moon is critical to human exploration, and it was first shared internally by the Gateway program office at Johnson Space Center in Houston. The document can be read here.

The five-page paper is not signed by any NASA official, nor is a point of contact listed. Additionally, because there are several grammatical errors and typos, it appears the document was rushed into production. Since it is not marked "for internal use only" and is written at a fairly general technical level, it seems meant for public consumption, including members of Congress amid criticism of the concept.

"I do not know whether it is intended as a formal statement of policy, but the fact that it was released anonymously means someone expected blowback," said a Washington, D.C.-based NASA source who had read the document and is familiar with the agency's plans to bring a human landing forward from 2028 to 2024. This source said the document accurately reflects what NASA's chief of human spaceflight, Bill Gerstenmaier, thinks about the Gateway and its role in human exploration. "It is certainly the most succinct summary of the thinking that goes into Gateway, and what the NASA HQ party line is, that I have read."

Why Gateway?

The document comes as Gerstenmaier is working to convince Vice President Mike Pence and the National Space Council, which have set a 2024 goal of landing on the Moon, that the Lunar Gateway is a key enabler to accomplishing that goal. Others have been telling Pence that, in reality, a Gateway will delay the landing by requiring additional development of space-worthy modules and billions of dollars of funding that could instead be invested in a lander to take humans to the lunar surface.

In summary, the document states: "Gateway supports the acceleration of landing Americans on the surface of the Moon in 2024 by providing a reusable command module and integration capabilities; the initial configuration of the Gateway acts as a waystation for the lunar surface mission, allowing the docking of Orion and checkout of lunar lander systems, as well as providing a temporary home for the crew who remains in orbit during the surface sortie."

However, Why Gateway? is also notable for some of its admissions. For example, the document acknowledges that NASA must place the lunar station in a high, eccentric orbit around the Moon—rather than low-lunar orbit, which makes the surface much more accessible—because the Orion spacecraft's service module as presently designed is under-powered. "Increasing its propulsive capabilities by more than 80 percent—from 1,100 to almost 2,000 meters per second to enter into and depart out of low lunar orbit—is not possible," the document states.

This may, however, be possible. The Orion capsule design is mature, but its service module—the aft end of the vehicle that provides power and propulsion—could be upgraded from the existing vehicle provided by the European Space Agency. NASA might contract with the US-based company to provide a more capable service module. Alternatively, the Space Launch System rocket's new upper stage, the Exploration Upper Stage, could be upgraded to include Integrated Vehicle Fluids technology developed by United Launch Alliance. In this case, the SLS rocket could fire its upper stage to exit low-Earth orbit and then fire it again near the Moon to inject Orion into a low-lunar orbit.

The document also provides some clarity about how long humans could stay on the lunar surface under the present Gateway approach—four days. This assumes a 21-day mission overall, which includes a five-day crew transit to Gateway in Orion, two days from Gateway to the Moon, three or four days on the surface, two days back to Gateway, and five days from the Gateway back to Earth. By contrast, the Apollo 17 mission in 1972 allowed astronauts to spend more than three days on the lunar surface but required just 12 days overall because the crew transited directly to and from low-lunar orbit.

Finally, Why Gateway? offers as a rationale the notion that since it will begin letting contracts for Gateway construction "in a matter of weeks," the project should be allowed to continue. "On balance, the near- and long-term benefits of pressing forward with the Gateway architecture far outweigh the risks of incurring substantial delays and inefficiencies that would inevitably result from a change to the architecture at this late date," the report states.

Two phases

Why Gateway? provides detail, for the first time publicly, about NASA's new plans for a two-phased approach to Gateway development. This change has occurred in the five weeks since Vice President Pence directed the agency to draw up plans to reach the lunar surface by 2024, rather than 2028.

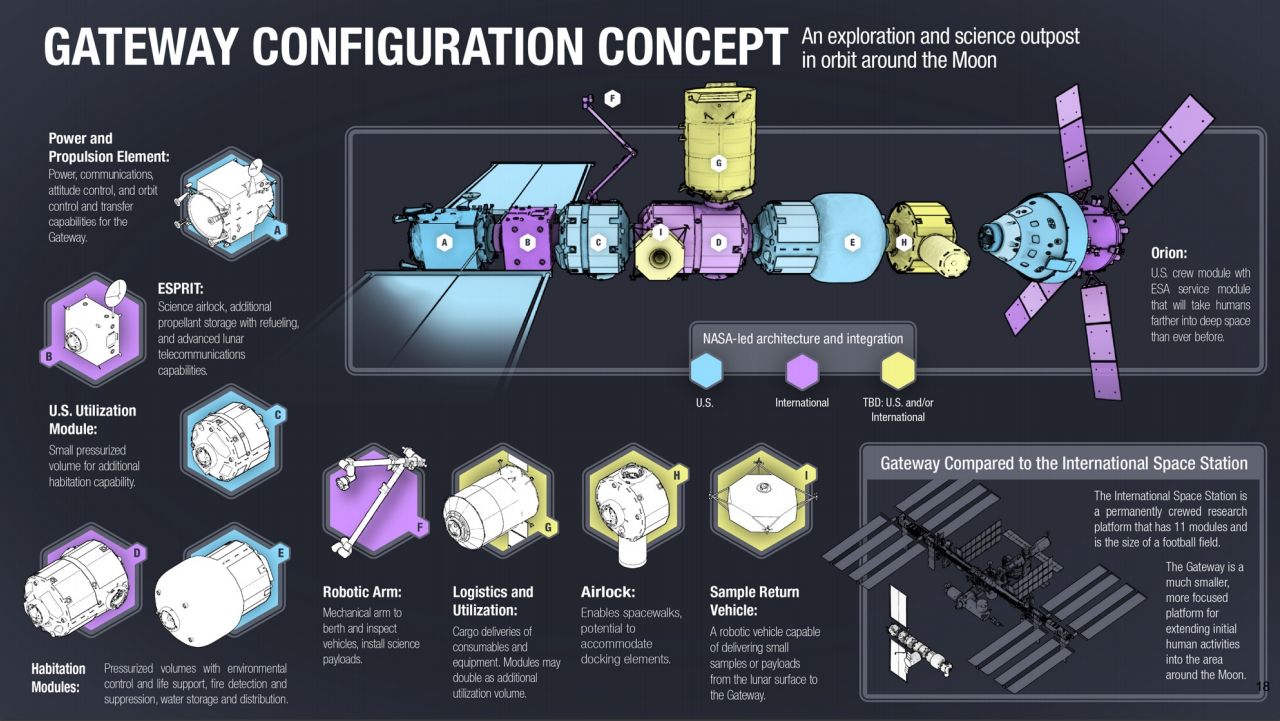

The plan calls for a "skinny" Gateway to enable the first lunar landings, which consists of a Power and Propulsion Element that will launch in 2022, and a "minimal habitation capability" that will launch in 2023. Both will launch on commercial rockets. "Phase 1 is driven exclusively by the administration’s priority to land the next American man and the first American woman on the Moon by 2024," the document states.

Publicly, at least, there has been general agreement among Gerstenmaier, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, and at least some officials at the White House on the utility of "Phase 1" for the lunar landing. It is not clear Congress fully supports this, however. And some aerospace officials have worried that NASA will still be building the Gateway, in orbit around the Moon, while China sends its taikonauts to the surface.

"It seems like the fastest and cheapest way to get to the lunar surface would be to simply fly to the surface directly and not spend the time or money to build a station in orbit around the Moon first," said Terry Virts, who testified at a recent National Space Council meeting about the Gateway and reviewed this report. "That strategy worked for the Apollo program, and 2024 is only five years away, which is an amazingly tight time frame to land people on the Moon. As context, 2014 was five years ago, and we were in the middle of the commercial crew program then. Now five years later it still hasn’t had its first launch to low-Earth orbit. The new goal is to make it to the Moon in that same time frame."

There is far less agreement on Phase 2, which would see the development of a large, robust Lunar Gateway—which some people have dubbed International Space Station 2.0 because of its size, the time it would require to construct, and the high cost to build and maintain such a station.

After 2024, Gerstenmaier prefers to build out the Lunar Gateway. However, the administration, including Pence and the National Space Council's executive secretary, Scott Pace, have talked instead about a lunar surface station at the South Pole. It is difficult to see how NASA could have both. White House officials must now be contemplating, if they let NASA start building a Gateway, whether they'll ever be able to stop that momentum in favor of a Moon base.