Archaeologists found microscopic traces of conifer resin and plant oils on bone fragments from skulls scattered just inside the walls of Le Cailar, a 2,500-year-old walled settlement near the Rhone River in southern France. That suggests that the heads had been embalmed with resin and plant oil before being displayed at the settlement, a practice described in ancient Roman texts and portrayed in sculptures at other Celtic sites across southern France. According to those texts and sculptures, it’s likely that the skulls belonged to defeated enemies.

“The head of the most famous enemy”

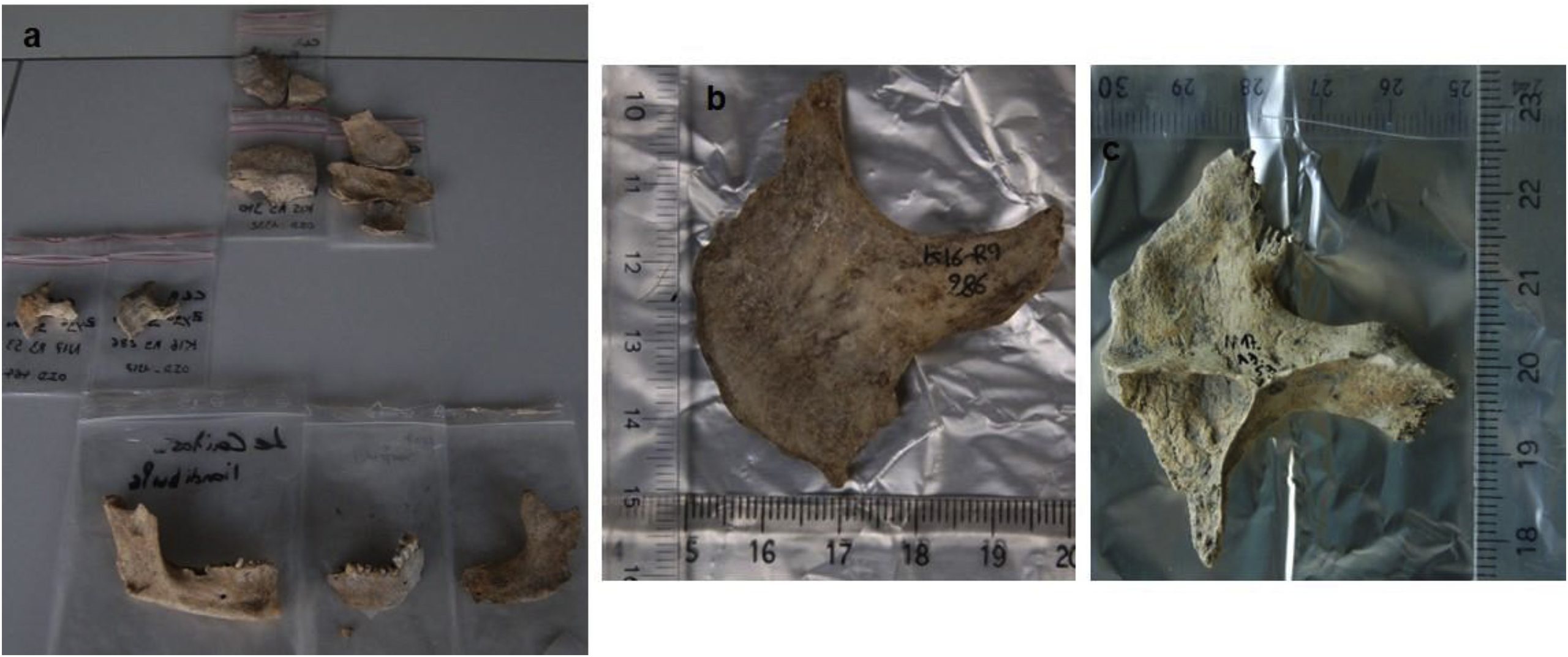

The fragments of at least a hundred human skulls lay buried in an open area just inside the town’s walls. They were mingled with weapons, coins, and broken pottery in a layer dating to 300 to 200 BCE, when the town was an Iron Age Celtic community. Many of the bones bear the telltale cut marks of decapitation but also evidence of the work that went into preparing these grisly trophies for display.

On some of the skulls, bone had been chipped, cut, or scraped away to widen the foramen magnum—the hole at the back of the skull where the spinal cord enters—probably to remove the brain. Scrape marks on the undersides of some of the skulls’ lower jaws suggest that ancient embalmers may also have removed the tongues.

The 1st-century BCE Greek historians Diodorus and Strabo both recorded the account of a Greek traveler to southern France around 100 BCE. He described Celtic fighters claiming the heads of the bravest and most renowned of their defeated enemies after a battle, then carrying them home to be embalmed and displayed. The heads of especially famous foes became prized items for the community.

“They never gave back the head belonging to the most famous and brave person, even for an equal weight of gold,” both historians wrote. Some archaeologists speculate that embalming may have kept those famous facial features recognizable, at least for a while. And it probably helped with the smell.

At some sites in southern France, archaeologists have found pillars or lintels where severed heads might have been displayed, but they have found no physical evidence of the kind of embalming described in the ancient texts—until now.

Friends, foes, or both?

Archaeologist Réjane Roure of the University Paul-Valéry Montpellier and her colleagues took small samples of bone from the surfaces of 11 fragmented human skulls at Le Cailar. They ground the samples into powder and ran them through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Along with cholesterols and fatty acids that could have come from the bone itself, six of the 11 skulls also contained traces of diterpenoic compounds—the molecules produced when conifer resins break down, especially under intense heat. Whether all of the fatty acids came from the bone or if some came from plant oils is hard to say. Five samples from animal skulls were used as a control group; these only contained cholesterol—no fatty acids, and no traces of conifer resin.

Interestingly, the display doesn’t seem to have been meant to terrify would-be attackers or taunt conquered foes. The skulls were found inside the walls of the fortified settlement, which suggests they were displayed for the benefit of the residents, not outsiders.

“As far as we know, it was a gathering place, where rituals or ceremony could have been organized,” Roure told Ars Technica. She added that archaeologists haven’t excavated enough of the ancient city to be sure what kinds of buildings or public spaces once stood nearby, so we don’t know if the severed heads were on display next to a military barracks, a temple, or the home of a prominent leader, for example. That kind of detail could reveal more about what the display actually meant to the people of Le Cailar. Was it a really over-the-top form of gloating, or were they honoring brave foes who had fought well?

There’s also a chance that some of the embalmed heads from Le Cailar belonged not to defeated enemies but to respected ancestors from the community itself. “Anthropology shows that often the societies who hunted heads kept, as well as enemies’ heads, ancestors’ ones,” Roure told Ars.

Archaeologist Martin Doppelt of the University of Chicago is studying isotopes of chemicals like strontium in the bones. He hopes to pinpoint where the former owners of the skulls came from. But that may not separate ancestors from enemies if the warring groups lived close by, Roure told Ars Technica.

Roure and her colleagues hope to analyze more skull fragments from Le Cailar and other sites. They hope the ancient bones will tell them whether embalming was a widespread practice or something unique to Le Cailar.

Journal of Archaeological Science, 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2018.09.011 (About DOIs).