“Black Friday” took on a darker connotation last week when US officials suddenly pushed forward the release date of climate scientists' latest report on the dangerous impacts of climate change in the United States. The report had been scheduled to come out in two weeks, but scientists were told to get it finalized on short notice so it could be released on a busy Friday instead.

(A major report on North America’s carbon cycle was released at the same time.)

The latest US National Climate Assessment report—available in an exceptionally readable format online—is a second volume, and it follows last year’s volume on the physical science of the climate system. The 2017 report was written by a large group of volunteer scientists and approved by federal agencies, and it summarized peer-reviewed climate research by explaining that climate change is real and the result of human activities.

The new report goes into what we know about the impacts climate change will have on life in the US. It’s also organized in a practical way: there are chapters covering particular types of communities, specific aspects of infrastructure, and each region of the country. This makes it easier to think about how multiple impacts can build on each other, making it easier for readers to find the most relevant sections.

Multiple impacts

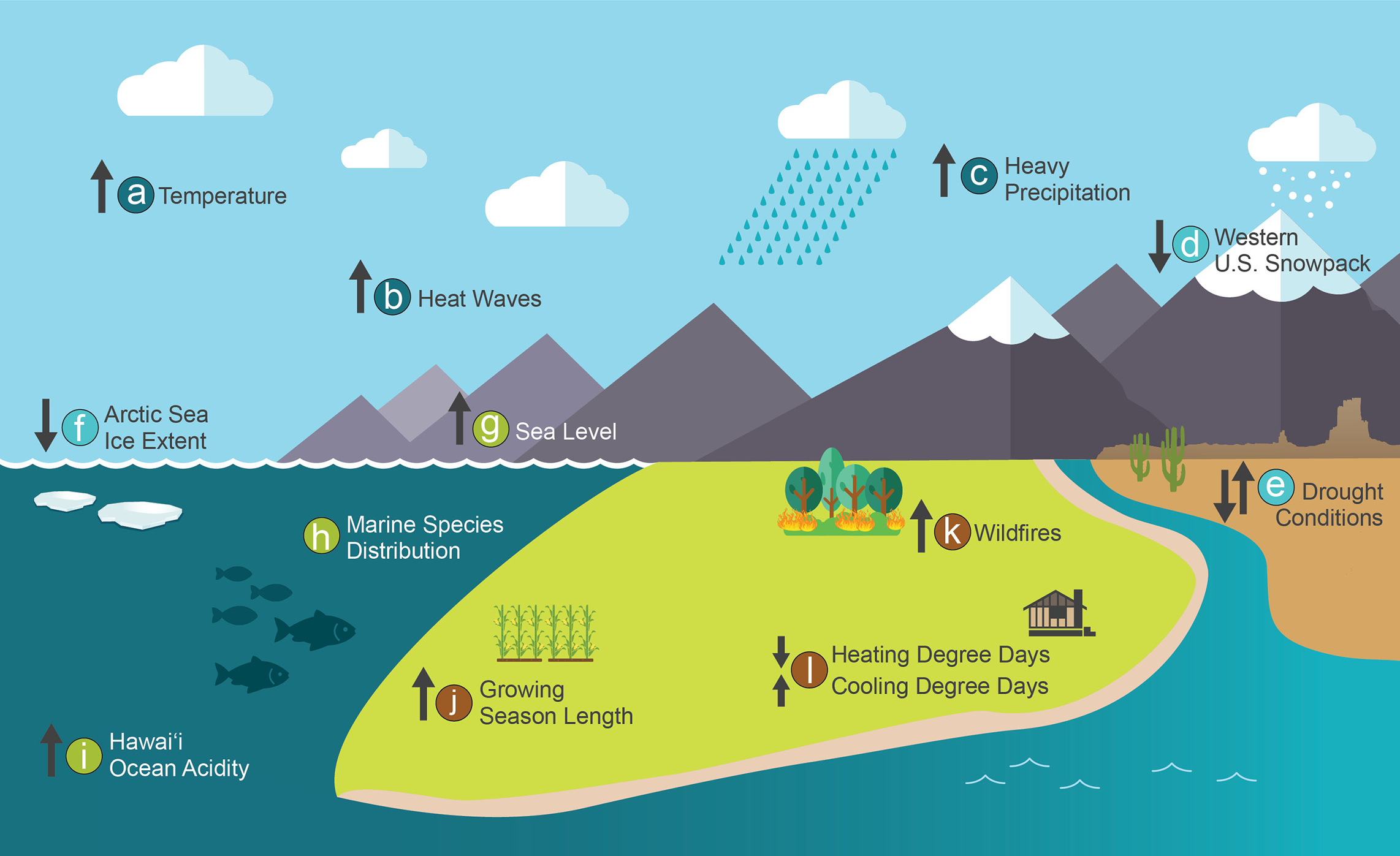

Take the energy system, for example. Coastal fuel transportation infrastructure and power plants can be threatened by sea level rise and storm damage. Inland, the grid is still threatened by flooding but from more intense rainstorms. And higher temperatures and more dangerous heat waves mean air conditioning demand will increase in many regions—while reducing the efficiency of transmission lines and stressing the cooling systems of some plants. For cities, the risks vary by region. Along the East Coast, sea level rise is a major concern, while the West is looking at the growing threat of wildfire. Heat waves threaten vulnerable populations in many cities, while air quality is also affected by fires, shifting pollen seasons, and even the influence of weather on air pollution. Human health impacts also extend to disease. Vectors like mosquitoes depend on wet weather and live in a range defined by temperature. Flash flooding can lead to water contamination by overwhelming urban drainage systems or enhancing agricultural runoff. And as for agriculture, the report adds effects on rural communities to the obvious discussion of crop yields. Indigenous communities, too, have risks that will affect their way of life. The report does touch on the ways that adapting to change—or taking action to limit global warming—can reduce these risks. Although many things cannot be quantified in economic terms, the report includes efforts to estimate economic impacts. A major EPA study, for example, estimated the economic damages of unmitigated warming would reach something like $500 billion per year for the US before the end of this century. Even partial emissions cuts that halt warming a few degrees Fahrenheit sooner could cut that almost in half.Off message

None of this will come as a surprise if you follow the published research closely—these reports are meant to summarize existing information. But that summary is a great resource that saves you the trouble of trawling through the thousands of dense studies it cites. The report lays out the impacts of climate change in specific, concrete terms. And the “TL;DR” statements are clear:“Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth[…] While mitigation and adaptation efforts have expanded substantially in the last four years, they do not yet approach the scale considered necessary to avoid substantial damages to the economy, environment, and human health over the coming decades.”The statement the White House put out in response to press questions about the report claims that it “is largely based on the most extreme scenario,” which is false. A range of future emissions scenarios—the standard set currently used in climate science—is presented everywhere in the report. The statement also claims that the next round of this report (which is released every few years) will “provide for a more transparent and data-driven process." It’s not clear how that’s possible, given that every detail in the report is drawn directly from the published, peer-reviewed research, and each chapter even contains a “Traceable Accounts” section that explains the reasoning and evidence behind each key summary statement. Every comment submitted during the review process is also available along with individual responses. In a recent interview with Axios, President Trump was asked about last year’s National Climate Assessment report. He answered that he had not seen it and did not accept its conclusion that human activities are clearly responsible for climate change. Trump answered, “I can also give you reports where people very much dispute that,” but no such report based on peer-reviewed science exists because the evidence and research provide no support for that position. UPDATE: On Monday, President Trump said of the report, "I’ve seen it, I’ve read some of it, and it’s fine." But when asked about the report's description of the great economic impacts of continued climate change, he answered, "I don't believe it."