Lizards are ancient creatures. They were around before the dinosaurs and persisted long after dinosaurs went extinct. We’ve now found they are 35 million years older than we thought they were.

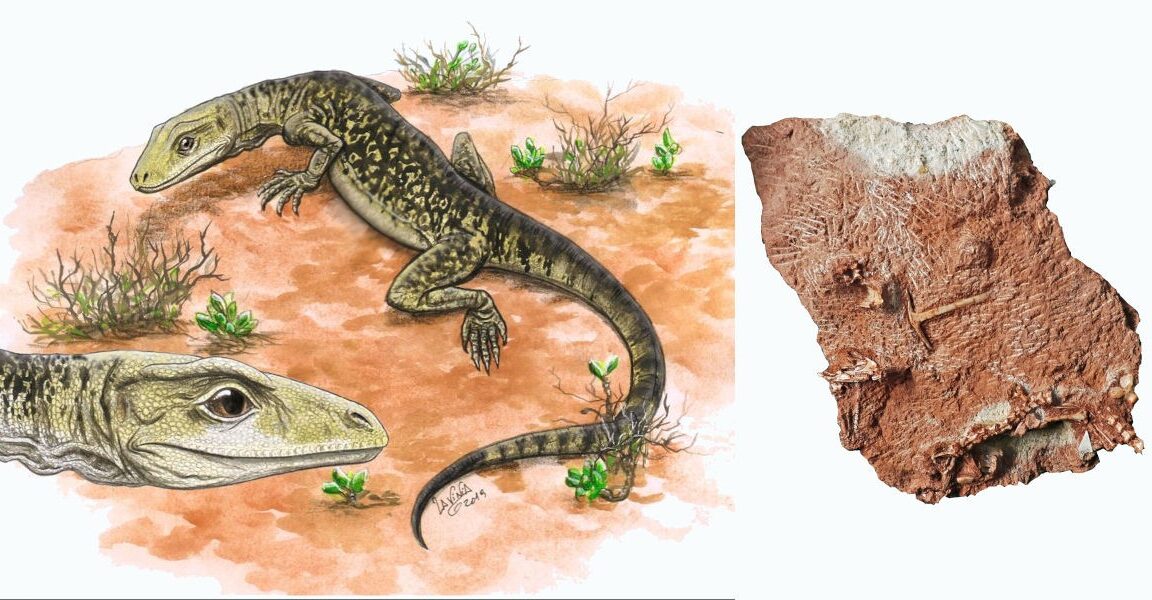

Cryptovaranoides microlanius was a tiny lizard that skittered around what is now southern England during the late Triassic, around 205 million years ago. It likely snapped up insects in its razor teeth (its name means “hidden lizard, small butcher”). But it wasn’t always considered a lizard. Previously, a group of researchers who studied the first fossil of the creature, or holotype, concluded that it was an archosaur, part of a group that includes the extinct dinosaurs and pterosaurs along with extant crocodilians and birds.

Now, another research team from the University of Bristol has analyzed that fossil and determined that Cryptovaranoides is not an archosaur but a lepidosaur, part of a larger order of reptiles that includes squamates, the reptile group that encompasses modern snakes and lizards. It is now also the oldest known squamate.

The misunderstandings about this species all come down to features in its bones that are squamate apomorphies. These are traits unique to squamates that were not present in their ancestral form, but evolved later. Certain forelimb bones, skull bones, jawbones, and even teeth of Cryptovaranoides share characteristics with those from both modern and extinct lizards.

Wait, what is that thing?

So what does the new team argue that the previous team that studied Cryptovaranoides gets wrong? The new paper argues that the interpretation of a few bones in particular stand out, especially the humerus and radius.

In the humerus of this lizard, structures called the ectepicondylar and entepicondylar foramina, along with the radial condyle, were either not considered or may have been misinterpreted. The entepicondylar foramen is an opening in the far end of the humerus, which is an upper arm bone in humans and upper forelimb bone in lizards. The ectepicondylar foramen is a structure on the outer side of the humerus where the extensor muscles attach, helping a lizard bend and straighten its legs. Both features are “often regarded as key lepidosaur and squamate characteristics,” the Bristol research team said in a study recently published in Royal Society Open Science.

The radial condyle, a round structure on the head of the radius (a lower forelimb bone) that allows the radius to move, is also an important skeletal characteristic in squamates but was not mentioned by the other team.

Another bone that wasn’t viewed as diagnostic in the earlier analysis was the septomaxilla. This small triangular bone is located on the upper jaw of a lizard, inside the nares or nasal openings. When the holotype was compared to a larger Cryptovaranoides skeleton that was unearthed later, both showed septomaxilla.

There was a bone that had been thought to be present but appears not to be. Most squamates, extant or extinct, lack a posterior projection on the back of the jugal bone, a skull bone that connects to muscles involved in chewing. After studying the original fossil, the Bristol team disputed the other team’s claim that there was possibly a projection there.

If it looks like a lizard…

In addition to pointing out problems with the interpretations made by the team that previously examined Cryptovaranoides, the Bristol researchers identified features of the animal that could only belong to a squamate, and they start in its deadly jaws.

Cryptovaranoides has pleurodont teeth, meaning they are fused to the jawbones instead of being held in place by sockets. This is a common occurrence in squamates but not so much in archosaurs. On the premaxilla (upper jawbone where the four incisive teeth are located) of Cryptovaranoides, there were four teeth on the right side and three on the left, something that was observed in both the initial fossil and a larger one discovered later. Cryptovaranoides was also the only animal from British fossil deposits that they knew to have seven incisive teeth. Both fossils also showed two bony growths near the back of the premaxilla, which distinguished them from archosaurs.

Something else that distinguishes Cryptovaranoides as a squamate is something called a choanal sulcus. The two openings in the back of the nasal passage of both reptiles and mammals are known as the choanae, and in the ancient lizard, each of these has a depression, or suclus. What it has in common with modern lizards here is that the sulcus becomes less deep further back, and as in modern squamates, the sulcus does not stretch across the facial bone that makes up part of the nasal cavity and palate. These features are, the Bristol team argues, “undoubtedly squamate in nature.”

On the skull of Cryptovaranoides was another unmistakable squamate feature. This is the large occipital recess, a hollow space in the back of its braincase, which appeared in squamates living around the late Triassic and early Jurassic.

The observations made by the Bristol team have reclassified Cryptovaranoides microlanius as a lizard, which makes squamates more ancient than we realized. The species is now considered to be a crown squamate, a member of the earliest clade, or group, descended from one common ancestor. This group includes all of the descendants of the first squamate ancestor. The Bristol team does not think there is any dispute that Cryptovaranoides is a squamate, and though they will continue analyzing the holotype, they do not think much, if anything, will change.

“Ctyptovaranoides is not a ‘problematic fossil,’” they said in the same study. “It is clearly a lepidosaur and a squamate.”

Royal Society Open Science, 2024. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.231874