European space officials will convene on Monday and Tuesday to discuss the future of space policy for the continent. The "Space Summit" gathering in Seville, Spain, will encompass several topics, including the future of launch.

"Seville will be a very decisive moment for space in Europe," said the director general of the European Space Agency, Josef Aschbacher, on the eve of the summit. "On launchers and on exploration, I expect ministers to really make very bold decisions. I certainly expect a paradigm shift on the launcher sector."

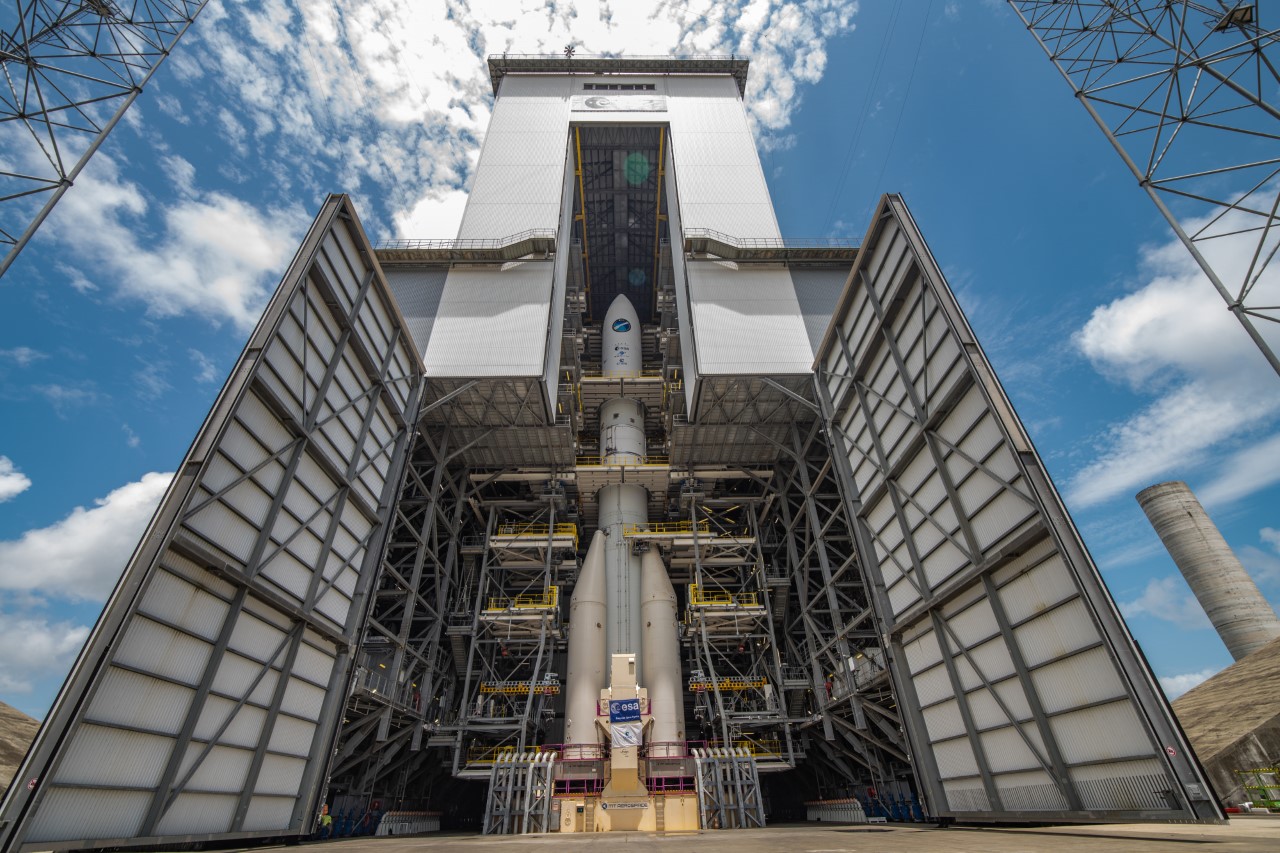

Aschbacher has previously described Europe's rocket predicament—the venerable Ariane 5 has retired, its replacement, Ariane 6, is not ready, and the smaller Vega C rocket is also having teething problems—as an acute crisis. Now, it's possible this crisis will lead to the breakup of a decades-long partnership in Europe, led by the nations of France, Germany, and Italy, to collaborate on the development of launch capabilities.

Back to its roots

The source of this crisis goes back about a decade when Europe was trying to determine what would come after the Ariane 5. That rocket was largely successful and provided Europe with its assured access to space. However, it was costly, and already it was losing commercial business to emerging competitors like SpaceX and its Falcon 9 booster.

The head of the German Aerospace Agency at the time, Jan Wörner, who would later lead the European Space Agency from 2015 to 2021, explained in an interview with Ars the decision-making involved in moving on from the Ariane 5. Germany, he said, pushed for a midlife evolution of the Ariane 5, modernizing elements of the rocket and bringing down its cost. This faster solution would buy the continent time to see whether the Falcon 9 was successful and consider whether the continent's next rocket should have a more radical upgrade.

By contrast, French officials preferred developing an entirely new but expendable rocket then, the Ariane 6. As a compromise in 2014, the chairman of Airbus, Tom Enders, emerged with an "industry" solution to build the Ariane 6 rocket. It would be a modernized version of the Ariane 5, and since industry would take the lead, it would be more cost-effective—50 percent cheaper than the Ariane 5 rocket.

As part of this compromise, Wörner said, Germany would develop the rocket's upper stage, the solid boosters would be developed by Italy, and the first stage in France. And so the European space powers remained bonded together.

The crisis comes

In the decade since this agreement was reached, there have been at least three factors that have precipitated a crisis in European launch. One is the rise of SpaceX, which, through its reusable Falcon 9 rocket, has come to dominate the commercial market with prices about half those offered by the Ariane rockets. Because it has optimized for speed, SpaceX can also launch far more frequently and efficiently than Europe.

Secondly, the Ariane 6 rocket has been delayed from its original goal of launching in 2020. Now, if hot-fire tests late this year go well, it is possible that the Ariane 6 rocket could make its debut launch by mid-2024, or about four years late. With the retirement of the Ariane 5, and the Russian Soyuz rocket off the market due to the war in Ukraine, Europe finds itself in the embarrassing position of relying on SpaceX to get some of its most valuable missions into orbit.

Finally, there is the cost issue. The goal of reducing operations costs by 50 percent has dropped to 40 percent. And now, citing inflation, European officials say those cost cuts are unsustainable. In fact, the Ariane 6 rocket's primary contractor, ArianeGroup—which is co-owned by Airbus and Safran—is asking for a significant subsidy to operate the rocket. It wants 350 million euros a year, which would essentially wipe out any cost savings from going to the Ariane 6 rocket.

So Europe has spent a decade and many billions of euros developing the Ariane 6 rocket, but all it has gotten it to date is a gap in the capability of launching satellites to orbit. This has ratcheted up tensions heading into Seville this week.

Big stakes in Seville

Late last week, the influential French newspaper Le Figaro published an eye-raising story suggesting that France, Germany, and Italy—as well as the other 19 member states of the European Space Agency—may be on the verge of an "implosion" when it comes to the development of rockets.

Many of these member nations are balking at paying ArianeGroup such a large, ongoing subsidy to operate the Ariane 6. One reason is that the bulk of the industrial work on these rockets is done in France and Germany, approximately 50 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

European rocket politics are complicated by the "geographic return rule," which states that each member nation must receive a proportional amount of contracts to the amount of funding it contributes to the space agency. "With the dawn of New Space and the delays in Ariane 6 launcher development, an ongoing debate has emerged about whether geo-return is consistent with the competition and competitiveness that is needed in Europe’s space industry," Aschbacher wrote in March.

Part of the Ariane 6 rocket's cost increase is being driven by suppliers in nations that know ESA must give them contracts to abide by the geographic return rule.

This week in Seville, officials with ESA will attempt to reach a new governance agreement to operate the Ariane 6 rocket, including subsidies. According to the article in Le Figaro, there are clear fault lines. Germany and France, in particular, may want to bet on commercial launch startups in their own countries. Italy, too, may want to focus on Avio's business, its native solid-rocket manufacturer.

It's possible, then, that ESA will, in the near future, become more like NASA. Rather than subsidizing the development of rockets like the Ariane 6 vehicle, it may simply buy them from the industry.