What's New

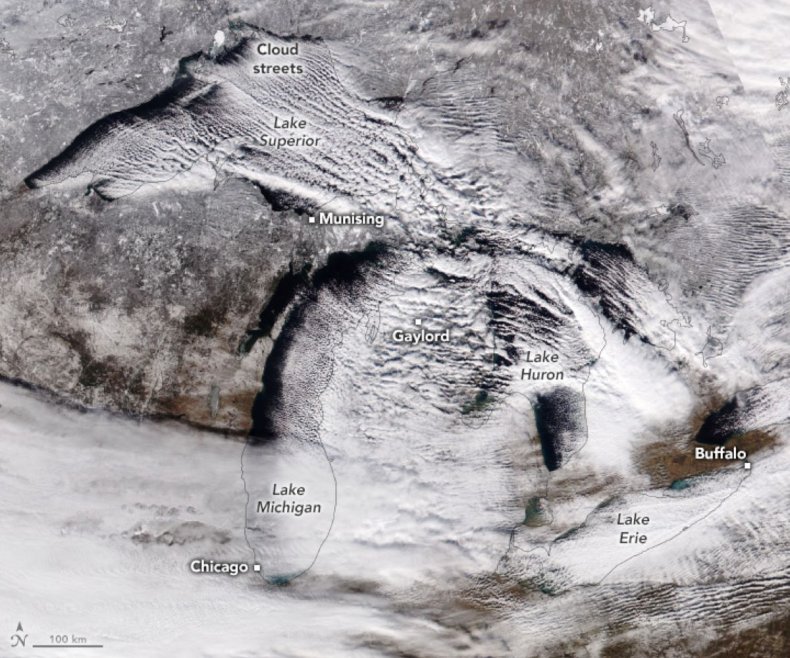

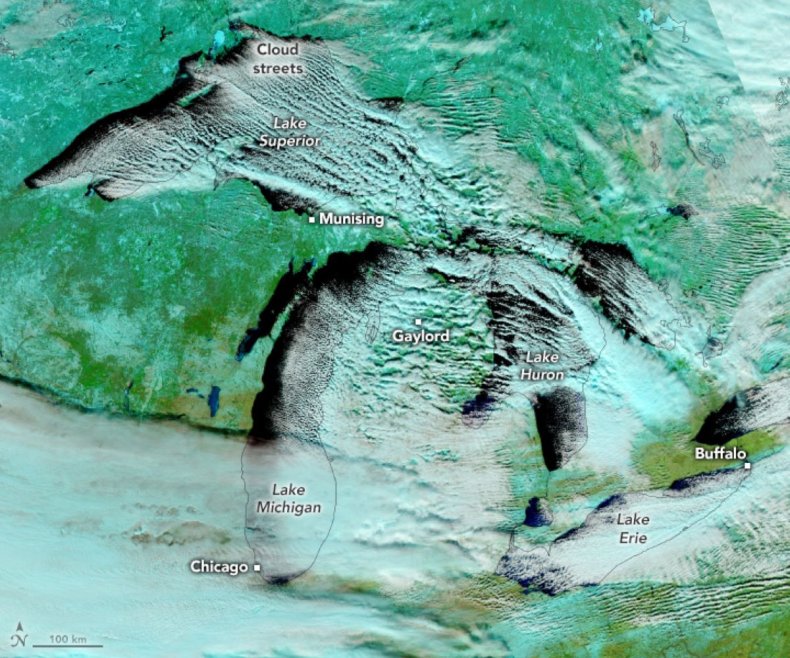

NASA's Earth Observatory has unveiled stunning satellite images of "cloud streets" forming over the Great Lakes, a phenomenon associated with lake-effect snow. Captured by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite on the NOAA-21 satellite, the images from December 12 reveal parallel cloud bands streaming across the lakes and heavy snow blanketing nearby regions. These natural color and false color images highlight the distinct patterns of clouds and snow.Drag slider

compare photos

Why It Matters

Lake-effect snow is a defining winter feature for communities near the Great Lakes, with significant implications for travel, infrastructure and safety. The recent snowfall buried towns in Michigan and New York under several feet of snow, while frigid temperatures and gusty winds disrupted life for millions.What To Know

The formation of cloud streets, sometimes called "streamers," occurs when cold, dry air moves over the warmer, unfrozen waters of the Great Lakes, picking up moisture and forming parallel bands of clouds. These bands, aligned with wind direction, can stretch over 100 miles and trigger intense snowfall when the moist air reaches the opposite shore. On rare occasions, they can stretch all the way from Lake Superior to the mid-Atlantic and New England coasts. Towns like Elma Center, New York, recorded up to 38 inches of snow, while parts of Michigan saw totals exceeding 17 inches over two days. Wind gusts reached 40 miles per hour, and wind chills dropped below 0 degrees in cities like Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Chicago. The false-color satellite image distinguishes clouds (white) from snow-covered land (light blue) and vegetation (bright green). It was created by combining both visible and infrared light. Lake-effect snow typically develops in narrow snow bands capable of producing 2 to 3 inches of snowfall per hour. These events are influenced by wind direction, temperature differences and geographic features. Under a cloud street, snowfall can be heavy, with AccuWeather describing scenes akin to "winter wonderland." Just a mile or two away, the skies can be clear and sunny, with no snow on the ground. While the phenomenon is common in late fall and winter, its intensity varies. Rare instances, like the 2014 Buffalo, New York, snowstorm that brought 88 inches of snow, demonstrate the potential for prolonged and extreme impacts.